South Africa has Mandela and Tutu. What does that mean about Palestine? Anything? Eleanor

12 September, 1998

I’m working on a speech I am to give to 350 school children on Monday on the history of apartheid. This is a chance to address all the comparisons that are made between South Africa and Palestine head-on. And to sound some warnings based on our own experiences and lessons learned.

As I prepare and comb through source material, I realize again what a miracle it really was—our peaceful transition. The violence leading up to the elections was mind numbing. Yet one of the big differences between here and South Africa is that South Africans never went to war with one another.1 Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. The PLO’s brutal hijackings. While purely numerically more blood was spilt in South Africa, it doesn’t feel like it was in the same spirit of implacable enmity and gruesome aggression. Or is that just my white naivety? The sheer determined violence of the IDF, the PLO, Hamas and Hezbollah2—I don’t think our armed struggle was of the same order. Or at least that’s not how I’ve heard Imaad and Mahdi, Sizwe and the others talk about it.

We had something that is lacking here. We had—still have—leaders of great vision and moral integrity. We had the spirit of Ubuntu3, of recognizing the humanity of the other even in the fight for justice. I’m aware of the sheer courage it must have taken to continue—by the Nats and the ANC—to negotiate in the teeth of all that violence. That’s not a courage or determination I see here. Here violence is used as a reason not to negotiate, to take yet more land, to squeeze yet harder; not a reason to negotiate, to solve the root cause of all of it: oppression, discrimination, occupation.

God, South Africa was a blessed and protected country.

We had Mandela. And Tutu.

There’s no Mandela, or Tutu, here.

But if we give up hope—then what possible future do these children have?

So I want to convey that part of fighting apartheid rested on understanding it was not some monolithic entity. Occupation, apartheid—they are human constructs. And we let them take up residence in our hearts, as Meredith and Naim would say. But they aren’t objective realities that cannot be changed. Built by humans, they can be deconstructed by humans. If there is a will.

We had that will in South Africa.

Is that will here?

I’m not so sure.

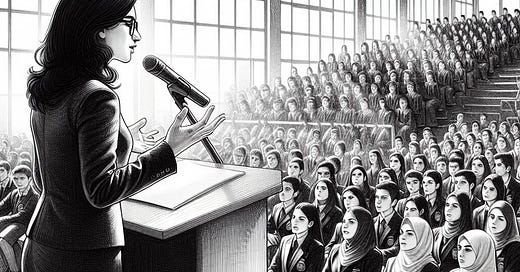

Nagla

Nagla watches Eleanor walk to the podium. This is her old school, and she’s proud to bring Eleanor here. But she’s also conflicted. As she’s come to learn more of Eleanor’s background, it seems to her that Eleanor’s life has been marked by a series of openings—open doors, open minds, open possibilities. In contrast, her own life and the lives of these school children have been defined by closures—closed borders, closed opportunities, closed futures.

She’s curious to hear how Eleanor has decided to approach this talk, though. Eleanor had peppered her with questions about the school as she prepared her speech, and Nagla had appreciated the effort. Still, however hard Eleanor tries, understanding isn’t the same as living. There are complexities and realities Eleanor just doesn’t know, cannot know, as a foreigner, no matter how good her intentions.

Nagla looks out on the crowd of young faces in their familiar maroon uniforms. The principal has gathered the entire secondary school as usual. The morning sun streaming through the tall windows of the school hall casts a warm glow over everyone. It’s strange—but good—to be back here.

"Good morning, everyone," Eleanor begins, her voice steady and clear. She doesn’t appear nervous. But then that doesn’t really surprise Nagla. Eleanor is similar in age to her, but Nagla’s always been impressed by how Eleanor carries herself with confidence. She seems quite at ease facing a room full of high-school students.

"Today, I want to talk to you about a very important part of history—one that is both painful and inspiring. I want to talk to you about apartheid in South Africa and what we can learn from it here in Palestine."

Nagla notes a collective shift in attention. The Europeans and Americans—they never say Palestine, just Palestinian Territories. But Eleanor and Francois, they always call it Palestine. Just as they call Israel, Israel.

She also shifts in her seat with a twinge of discomfort. Maybe she’s being oversensitive, but Eleanor’s words carry a hint of presumption: that there’s a lesson here Palestinians haven’t learned, a wisdom they must import from abroad. She feels a familiar flicker of resentment at how dependent her people are on international support if they are ever to win their freedom, and irritation at how they are made to pay for that support by being told how they’re supposed to earn their freedom. It’s like telling a woman “if you want your husband to stop beating you, be a more obedient wife.” It’s one reason Nagla has no intention of ever being married.

"South Africa, my home country,” Eleanor continues as Nagla brings her attention back to the present, “underwent a period of intense racial segregation and discrimination known as apartheid. It was a system designed to keep people apart based on the color of their skin. Black South Africans were treated as second-class citizens in their own country." Nagla sees students and teachers nodding. They know exactly what Eleanor is talking about.

"But despite the violence and the oppression, something extraordinary happened," Eleanor carries on, her voice clear, her delivery smooth. "South Africa made a peaceful transition to democracy. This was nothing short of a miracle, given the bloodshed and brutality that preceded the elections. Today I want to tell you the story of how that happened. And what parallels I see between my home country and yours.”

As Eleanor carries on talking, a hush falls over the room. From her vantage point to one side of the hall, Nagla sees how all eyes are on Eleanor. Everyone is listening intently. The school has always had regular international visitors and speakers, but many of them drone on and mouth platitudes. The students are always respectful and polite, but she remembers the feeling, when she was in their place, of how those visitors never seemed to get the reality of being Palestinian. Eleanor at least seems to try to. And so she has their attention. She’s also sharing stories about her own youth in South Africa, and how being here in Palestine has helped her to understand better what it was like to be black in South Africa.

Nagla’s impressed. Eleanor’s unafraid to share how Palestinians have helped her to understand her own country better. But she still feels conflicted. As Eleanor shares the story of South Africa’s negotiations even as violence continued to reign, she speaks with an optimism that borders on naivety. Does she really think that courage and dialogue alone can overcome the implacable force of an occupying power?

"One of the key differences between South Africa and other places of conflict," she hears Eleanor saying now, "was the nature of anti-apartheid struggle. Yes, it was violent and intense. Yes, resistance to apartheid was met with more violence from the apartheid government. But it was also different. The anti-apartheid struggle came to have broad international support. Not at first, but over time. And a big reason for that was our leaders—people like Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu."

Nagla notes the subtle commentary Eleanor is making. As a child of the Intifada herself, she has far more trust and respect for local Palestinian leaders than the returned PLO leaders. But the way Eleanor talks about Mandela and Tutu, it’s as if she’s saying, Why don’t you have leaders like that? Nagla knows the story is more complicated. There’s no shortage of courage or moral integrity here, but even now, even with the Oslo Accords, there’s still a relentless, crushing occupation that doesn’t leave much room for the kind of leadership Eleanor is extolling.

"Mandela and Tutu were leaders of great vision and moral integrity. They had the courage to negotiate, even in the face of violence. They understood that the only way to truly end the conflict was through dialogue and reconciliation." Nagla sees teachers nodding. This international school is founded on principles of non-violence. "But here, in the conflict between Israel and Palestine, we see something different. Violence is often used as a reason not to negotiate, to take more land, to impose more restrictions, to detain more people and expand the settlements still more. The root cause of the conflict—oppression, discrimination, occupation—remains unaddressed." Nagla’s eyes widen in surprise. She knows Eleanor can be direct. She hadn’t expected Eleanor to be quite so direct, even here.

"But here's the thing," Eleanor continues, as if she hasn’t said anything unusual, "apartheid and occupation are human constructs. They are not unchangeable. They were built by humans, and they can be dismantled by humans, if there is the will to do so. In South Africa, we had that will."

Eleanor pauses, letting her words hang in the air for a moment. "The question we need to ask ourselves is: is that will present here? Do we have the same vision and courage as Mandela and Tutu? Can we all, wherever we are in the world, contribute to a future where peace and justice prevail? Or will we let our hearts be occupied by hatred, or even worse, disinterest?" Nagla shifts again in her seat. Her discomfort is palpable. Eleanor makes it sound so simple, and it’s anything but.

“I believe,” Eleanor continues, unaware of Nagla’s skepticism, “from what I have learned about your school, that you all can be leaders like Mandela and Tutu. It starts with being aware of how we ourselves can be led away from compassion towards hate, and refusing to let the occupation live in our hearts, even as it lives in our lives."

The hall is silent for a moment as Eleanor concludes her speech. Then applause, enthusiastic and not just polite, breaks out. Nagla senses a mirroring of her own mix of emotions, her own internal conflict, to what Eleanor has said, among the students and teachers. Her candid reflections on apartheid and occupation resonated deeply. Nagla feels understood. But also uncomfortably challenged and even a bit angry. Angry at the unfairness of a foreigner, once again, exhorting them, the occupied and the oppressed to “do better”, to rise above the cycle of anger that the occupation fosters. It’s not an easy thing to do. The hatred towards Israel, to all that it has done, all that it continues to do, to her people and her country, is powerful. It feels wrong that the oppressed should be called upon to be the ones to break the chains of hatred.

But isn’t the alternative just more of the same? whispers a corner of Nagla’s mind. The cycle can be broken, Eleanor was saying, but it starts from within.

Nagla wishes Eleanor was speaking to Israelis, not just Palestinians.

But then again, maybe she was.

Bonus Material

The troublesome hero-ification of Mandela

Ubuntu: more than a word

March Indie Collective

Other Indie authors have been so kind to me, sending me MANY new readers as they let their readers know of On the Road to Jericho. Let’s return the favor. Check out March’s Indie collective.

(And yes, please do click the link! It builds my reputation as an indie author who supports other indie authors, so 🙏 in advance. Every click counts. Thank you!)

Eleanor is forgetting her history. There were the colonial wars: the Boer Wars (1880-1881, 1899-1901), the Anglo-Zulu war (1879), and the Cape Frontier wars (1779-1879) to name a few; and the Cold War proxy wars in Namibia (1966-1989) and Angola (1975-2002) in which the apartheid government interfered. Resistance to apartheid (1948-1990) ranged from non-violent civil disobedience, to armed and violent resistance and guerilla warfare.

Author’s note: It is uncomfortable to let this phrase—as written in my journals at the time—stand. But I decided it was more important to reflect that even the best of intentions are not proof against being influenced by propaganda, than to make Eleanor look better than she was. Even in 1998, and even using conservative figures, Israel had killed vastly more people, mostly civilians, than the PLO, Hamas and Hezbollah combined. See https://www.ochaopt.org/data/casualties and https://www.btselem.org/statistics. Eleanor's statement conveys a moral equivalence between the army of a full nation state and occupying power, and resistance to it.

African humanist philosophy. In the words of Archbishop Desmond Tutu: “In Xhosa, we say, ‘Umntu ngumtu ngabantu’. This expression is very difficult to render in English, but we could translate it by saying, ‘A person is a person through other persons.’ We need other human beings for us to learn how to be human, for none of us comes fully formed into the world. We would not know how to talk, to walk, to think, to eat as human beings unless we learned how to do these things from other human beings. Ubuntu is the essence of being human. It speaks of how my humanity is caught up and bound up inextricably with yours. It says, not as Descartes did, “I think, therefore I am” but rather, “I am because I belong.” I need other human beings in order to be human. The completely self-sufficient human being is subhuman. I can be me only if you are fully you. We are created for a delicate network of relationships, of interdependence with our fellow human beings, with the rest of creation. I have gifts that you don’t have, and you have gifts that I don’t have. We are different in order to know our need of each other. To be human is to be dependent.” Desmond Mpilo Tutu, ‘Ubuntu: On the Nature of Human Community’, in God is Not A Christian (Rider 2011).

This is a great chapter, really demonstrating how well meaning and supportive, but still wildly idealistic and uninformed she was I think. The additional notes added great perspective!